OPINION: THE SCALE UP CHALLENGE

15 November 2025

The UK is great at starting companies. We need to get better at growing them

James Codling on what it really takes to scale — and why it matters for the UK

- - -

I am asked fairly regularly what I mean when I describe a company as a scale-up. The term is used so casually now that it has started to lose meaning. It is thrown around to describe everything from a newly funded Series A business to a global growth success. No wonder there is confusion.

Start-up, by contrast, is a clearer idea: a very early stage, a small founding team, a product forming in real time, a pitch deck that is still part aspiration, part experiment. The UK is genuinely excellent at this. SEIS and EIS have helped build an entrepreneurial culture that encourages people to start companies. Our universities continue to produce strong research-led innovation and technical talent. The UK now ranks third in the world for the number of start-ups created each year.¹ The initial spark, the invention, the early momentum — we are good at that.

Where the UK struggles is what happens next.

There is a formal definition of a scale-up, used by the OECD and the UK ScaleUp Institute: a company growing revenue or headcount by 20% a year for three years from a base of at least ten employees.² In practice, though, the term is more often used to describe the stage where a business has found product-market fit and a repeatable go-to-market strategy, and is now building the organisational capacity to grow. Start-ups are proving whether something works; scale-ups are proving whether they can do it repeatedly and at increasing scale.

And this is where the UK has a problem. We produce a large number of promising early stage companies, but too few make it through the next phase of growth.

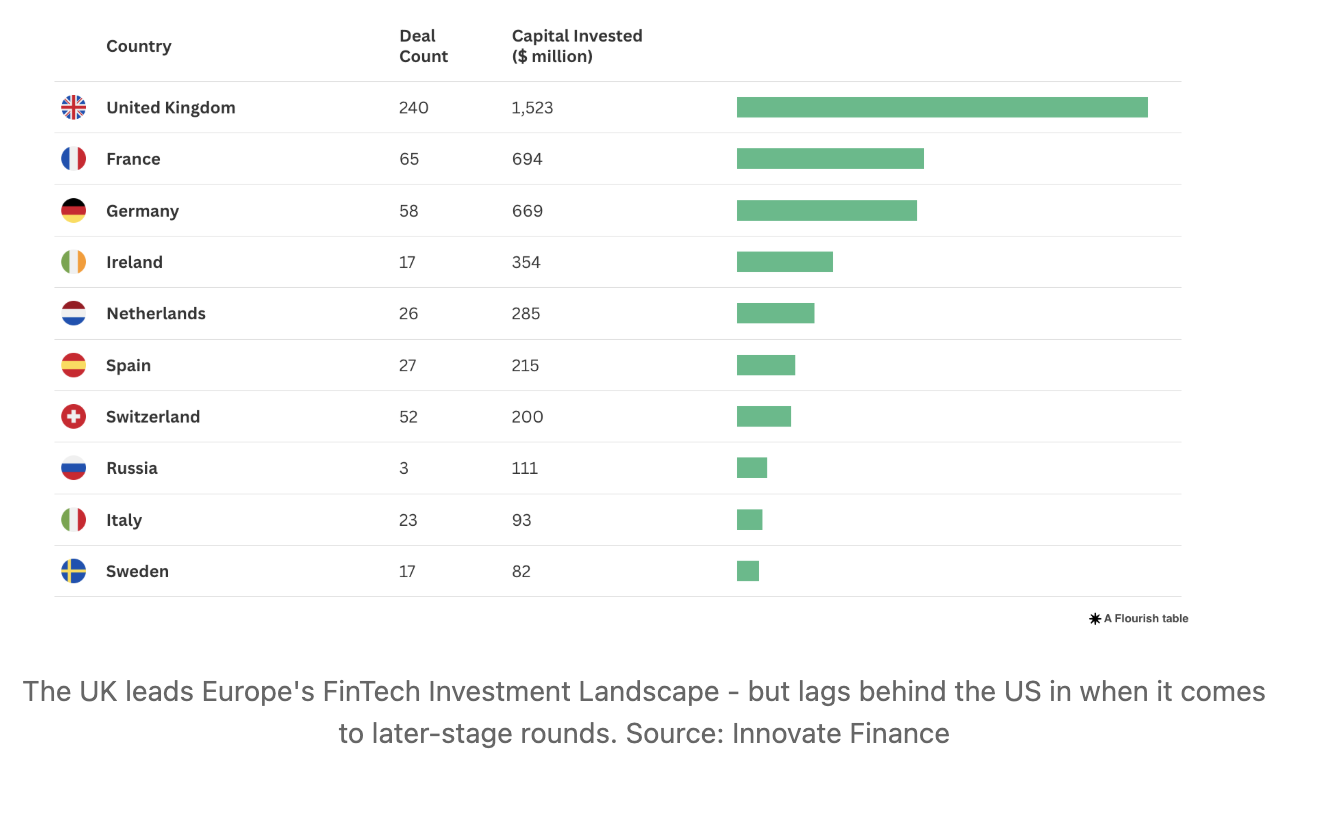

In FinTech, the UK is Europe’s dominant hub, attracting more investment than the rest of the continent combined and second only to the United States. Yet most of this activity remains concentrated at the earliest stages, with a relative shortage of larger, late-stage rounds compared with the US.³

AI shows the same pattern: the UK is the world’s third-largest AI market after the US and China, but most UK AI companies remain small. Government-commissioned reviews warn that without deeper scale-up finance, the UK risks becoming an “IP farm” for other countries rather than a home for globally scaled firms.⁴

None of this points to a lack of talent or ingenuity. It points to a structural funding gap.

Once a company reaches Series A, it has achieved something important — but it has not yet proven that it can scale. Yet the capital available to support this next, critical stage is limited. Most Series A funds are not structured to continue deploying heavily into later rounds, while many growth-stage investors only enter at or after Series B, when revenue, international footprint and management maturity are already demonstrated. The result is a no-man’s-land where companies that are full of potential cannot access the patient capital required to turn that potential into scale.

The consequence, too often, is early acquisition. In FinTech and enterprise SaaS, we see highly promising companies sold to larger international players before they have had the chance to grow into sector leaders. The UK becomes an incubator and a transfer hub, rather than a producer of global market leaders.

The scale-up stage is where the real economic value sits. This is where jobs multiply, where supply chains form, where domestic intellectual property hardens into export advantage. Scale-ups are not just company outcomes. They are national strategic assets.

But scaling is not simply “more of the same”. It requires a step change in how the organisation operates. The founder role moves from improvisation to discipline, from individual execution to leadership through others. Functional teams expand and talent needs shift from motivated generalists to specialists. Operational excellence becomes as important as product innovation. The company must learn to do what it does well — repeatedly, predictably, efficiently. And for UK companies, scaling almost always involves international expansion. As an island economy, domestic scale alone is rarely enough for full potential. New markets are not optional. They are the growth plan.

All of this requires capital that is patient enough to support the journey. Yet UK pension funds currently allocate less than 1% to venture and growth investment, compared with 5 to 10% in the US and Canada.⁵ The Mansion House reforms announced are positive signals, but unless they translate into actual allocation, they will not change outcomes.

At Volution we invest deliberately at this scale-up inflection point. We provide capital alongside operational and international support. We work with management teams to strengthen unit economics, deepen repeatability and expand into new markets. Asia, in particular, continues to offer meaningful growth opportunities in FinTech and AI-driven enterprise software. Our role is to help companies scale into those markets deliberately rather than reactively.

The UK has built a strong engine for starting companies. The competitive advantage now lies in whether we can build an economy that consistently grows them. Strength in scaling is what turns innovation into productivity, exports and national capability. This is the lever that matters.

James Codling, Managing Partner

This blog was orignally posted on LinkedIn.

Sources

-

Startup Genome

-

OECD / ScaleUp Institute

-

Innovate Finance; British Business Bank

-

DBT; CDEI–DCMS; House of Lords Communications & Digital Committee

-

HM Treasury, Mansion House Reforms

Share on Social Media